UNICEF India: planning for success

Resource mobilisation and partnerships chief Richard Beighton explains how UNICEF India accelerated fundraising step by step.

UNICEF has been addressing children’s rights due to inequality and poverty in developing countries but more recently it has been raising funding from within many of the countries where it does programme work – countries such as Argentina, Malaysia and India.

In 2018, UNICEF India was struggling to fund its work in India. “We had a huge long-term funding gap,” says Richard Beighton, then resource mobilisation and partnerships chief at UNICEF India. “We were only raising a few million dollars a year from within India, while international governmental overseas development funding was continually being reduced.”

The situation was unsustainable. But Beighton and his team realised the huge opportunity India offered for fundraising. “We knew that what we had been raising was a drop in the ocean and the potential was huge. India has a population of 1.4 billion people, with a rapidly growing middle-class, more than in the whole of Europe.”

“We also knew that Indians wanted to support our work in their country – there are many success stories from over the years (for example under-five deaths have fallen 25% in just five years) but there is so much more to do in a country of this complexity and this size.”

“While there is a cultural tradition of giving in the country, both at individual and corporate level, there was a recognised need for a strategic and sustainable approach to channel this generosity into a regular behaviour, leading to tangible and meaningful outcomes.”

Four-point plan

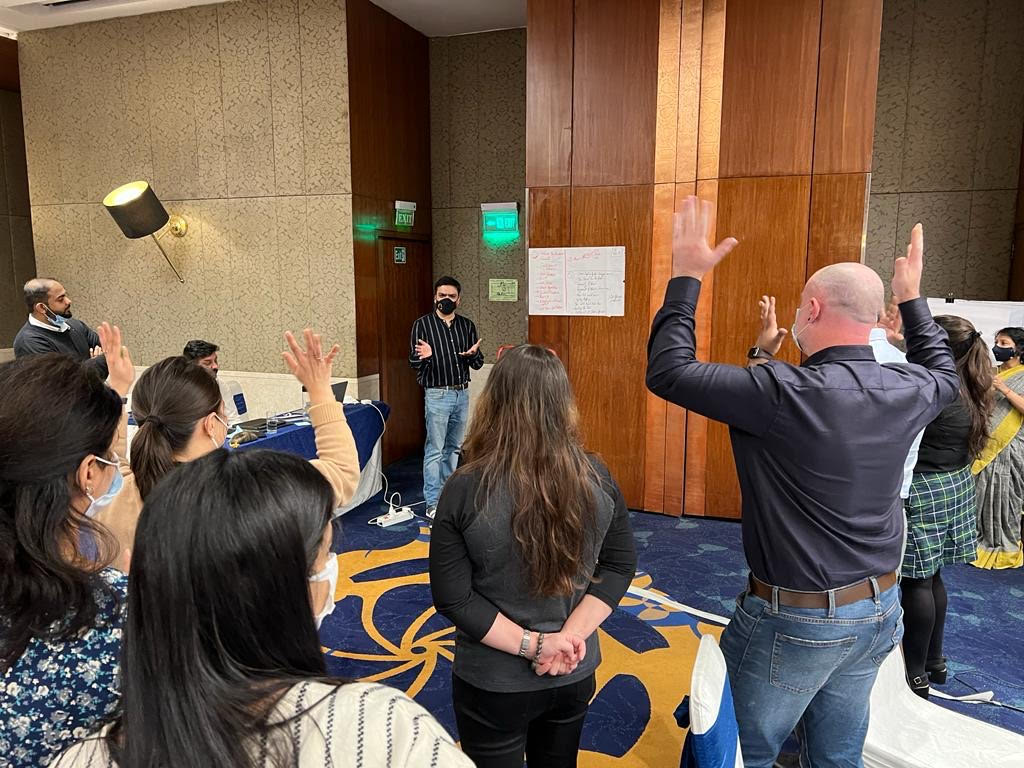

With learning from a Revolutionise workshop in mind, Beighton started to put in place a fundraising strategy that aimed to realise the enormous potential in India based around four core areas: plan, people, partners and investment funding.

Formulating the initial plan involved stepping back and looking at what was achievable, says Beighton. At the time, UNICEF had around 35,000 individual regular donors, with an average year-on-year net gain of around 14,000. “We set a target of reaching 500,000 regular givers within five years,” he explains. “It was ambitious, but it didn’t feel entirely unattainable. We knew it was possible, just incredibly difficult. The challenge was to do it in that timeframe.”

High-value streams such major donors and corporates were also factored in and the plan began to take shape. “We had no major donor programme and only a few corporate partners, and they were actually on the decline. So, we identified those as areas of potential growth as well.”

With these goals in mind, investment in salaries was prioritised and an excellent fundraising team with the right expertise was assembled.

“We had an ambitious plan and rightfully so given the potential that a country such as India held. But any plan is only as good as the people who execute it. So, we went on a planned and rigorous approach to find the right talent to join our fundraising force.”

“While prior sector experience was a positive factor, our primary criteria focused on outcome-oriented individuals, skilled in relationship-building, and most importantly, those who resonated with the mission of driving results for children. We also ensured that our team comprised not just generalists but specialists, each contributing unique skills from their experience to roll out our fundraising plan in the most effective manner.”

Fundraising partnerships

With the plan and people in place, the next step was to secure partners to make it happen. Finding the right partners was going to be key to the success of the four-point plan.

“It was important right from the start that anyone we spoke to understood that we didn’t just want an agency, we needed a partner,” explains Beighton. “We wanted sustainability and high value.”

“But nobody was doing face to face in India. There was only one charity doing DRTV and a whole load of tele-marketing agencies, none of which were doing it very well.”

Beighton turned to the commercial sector and sought to partner with a direct dialogue specialist, SDI, that was then selling credit cards and insurance. This let it use its skills and network to add fundraising to its portfolio.

“The goal was to learn from industry best practices in direct and offline marketing, even beyond the social sector, to implement effective strategies for face-to-face fundraising,” says Beighton.

By bringing in the commercial specialist, which employed up to 700 face-to-face fundraisers, within 12 months of starting, UNICEF India saw recruitment jump from 900 a month to over 9,000.

Corporate and investment funding partnerships

Up until then, UNICEF India’s corporate fundraising had been minimal and purely transactional. “Once again, we saw a tremendous opportunity to grow at scale,” says Beighton, citing the fact that under the corporate law large companies in India have to spend 2% of their profits on corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities such as “improving education” or “safeguarding environmental sustainability”.

Although UNICEF cannot directly apply for this funding, it creates a philanthropic context in which to engage corporate leaders.

“These companies have millions to spend on CSR but they have massive marketing budgets and are owned by some of the richest people in the world, many of whom are highly philanthropic. But we hadn’t gone out there to inspire them to work with UNICEF.”

On the high-value funding side, foundations were another missed opportunity.

“We wanted to create dream outcomes at scale for all potential high-value partners; present them with a vision that they could really buy into,” continues Beighton. “Instead of going in and just asking for money, we wanted to offer them the chance to unite with UNICEF in driving towards a huge tangible outcome.”

One such initiative was the government’s End Anemia project. “This was a gamechanger. We were talking to a foundation about reducing anemia and failing to excite them, but once we turned it into a joint mission to help End Anemia, instead of looking at the proposal and talking about money and law and contracts and so on, they started talking about the vision.

“We never asked for an amount. We didn’t have to because from then they wanted to get involved. In the corporate sector companies wanted to put their names to outcomes like this. They wanted their customers to know that’s what they are doing.”

“It was about engaging them in developing a wider view. It wasn’t primarily about how to increase our funding; instead, we led joint development of initiatives to create significant impact in the lives of children in India that would only happen by working together. Nobody gives to a charity; they give to the outcomes that you’re working towards or, even better, outcomes that they can get involved in.”

Public support

When it came to securing public support and backing, Beighton and his team paid close attention to fundraising messaging and adopted an inclusive approach. Unlike the UK where UNICEF works primarily for overseas development, in India it is working on issues at home. Governments and the public don’t like to be constantly reminded of issues such as high infant mortality and child malnutrition rates or failings in the health system.

“And in a country such as India it is also over simplistic and unfair,” adds Beighton. “Even from a behavioural science perspective, humans exhibit an inclination towards affiliating with a winning team, where they can see the tangible impact of their efforts leading to favourable outcomes.”

So it was important to reposition from talking only about issues to focusing on national successes. India is developing rapidly and is rightly proud of many achievements, for example its rapid and hugely successful response to COVID-19.

“We looked for the positives playing into a sense of national pride, and linked it to a bigger dream for children of India that we all could together achieve,” continues Beighton. “The truth was that infant mortality rates had fallen in India by 25% over the last five years, with the relentless efforts of various stakeholders involved. That is a tremendous achievement.

So, we focused our fundraising around that, calling for participation to work towards a common goal. We thought: let’s not start with the issue. Let’s start with the success. It was about instigating national pride and instilling a sense of inclusive action by saying: “Hey, we’ve done a lot. There’s a bit more to do. Let’s all get together and do it”.

This formed the basis of a sustained face-to-face campaign, as well as developing a relationship which set the scene for UNICEF to become a partner in advising on the $650m being spent by government-owned private companies on CSR initiatives.

Fundraising achievements

Since the initiatives began, India has become UNICEF’s fastest-growing country in terms of fundraising, recruiting 123,000 new regular donors in 2022 and looking to grow this still further. Income from individuals has thus grown thirteen-fold.

Meanwhile in high-value fundraising the team has signed their first major donors, attracted Indian and international corporate partners and raised significant funding from foundations, giving the same growth rate of thirteen-fold.

“The fundamental key to success was starting with a vision of where we could potentially get to and not where we started. We haven’t reached the 500,000 target yet but, had we not been ambitious, we might have only dared aim for three or even four-fold increases and never dreamed of finishing where we did” says Beighton.

“It was never just about the money,” he adds. “It was always about helping the children of India and giving our supporters a role to play in that mission and inspiring them to join or stay connected. We would never just ask for money. Fundraisers often talk about not seeing donors as just chequebooks and then we treat them like chequebooks. If you can inspire your supporters, you won’t have to ask.”

Key learnings

- Big scale delivered by small activities – have big ambitions but break them down into manageable chunks. Aim to be in the top 10% of comparators for every KPI and the wins will add up to being best in class.

- Keep the plan simple – don’t spend a lot of time in the planning stage. Just go out and do it, see what happens and then amend as needed.

- Set targets but don’t be afraid to miss them – things can change, so be prepared to adapt and revisit what your goals are.

- Focus on audience centricity – give donors a role in achieving tangible outcomes.